pressure rising

Some things wilt when you try to force them to bloom.

March 26, 2020

Kings Heath, Birmingham

The drizzle had been falling since morning—soft but relentless, like a thought she couldn’t shake. Outside the window, the world looked fogged over and flat, like someone had turned down the volume on real life.

Clara stirred pasta on the hob, half-listening to the radio. A clipped BBC voice was saying something about non-essential travel. Then the Chancellor—solemn, synthetic—repeating phrases like “national effort” and “support packages.” She muted it but left it on, clinging to the thin connection to the outside, even as she rejected its message.

Sam was on the sofa, cross-legged, phone propped on his knee, humming tunelessly. The room had filled with the low buzz of both of them—phones, pots, half-finished conversations. The flat wasn’t large, but it had once held a quietness that asked for nothing—she missed that now.

They’d known each other six weeks. A drink at a pub she never usually went to. Then a walk, then a night, then another. It had started with a click—the unexpected kind. He made her laugh, made her feel wanted—a feeling that hadn’t happened in a while. His attention had been full, bright, generous. She hadn’t planned on anything serious. But she hadn’t said no, either.

After three years of being single—after the slow dismantling of a long-term relationship that had left her with a flat full of books and a kind of ambient loneliness—the suddenness of Sam had felt like proof: that she was still findable.

Then lockdown. He hadn’t wanted to return to his shared house. His flatmates were fleeing back to family homes; one had a partner with asthma, the other was already halfway to Somerset. She told herself it was sensible—they’d been spending most nights together anyway. But it was a lie. This move-in would never have happened under normal circumstances.

Now here he was, barefoot in her living room, trying not to be in the way.

“I’ll be ten minutes,” she said.

He looked up and smiled. “Cool.”

She drained the pasta, let the steam rise. The sauce was something with aubergine and anchovy—the smell, usually so comforting, felt overly pungent, clinging to the curtains and her hair. She hadn’t cooked for anyone in months. It had felt purposeful, at first—a gesture for a lover. Now, it felt like a role she hadn't auditioned for. The wooden spoon in her hand felt less like a tool for seduction and more like a utensil for feeding someone who needed looking after.

They ate by the front window. Outside, a Tesco queue snaked along the pavement, everyone spaced like punctuation. The street, once noisy and close, was now cautious, aerated. Inside, the candle she’d lit flickered against the wine glasses.

“This is banging,” Sam said. “Seriously. Like MasterChef level.”

“It’s just pasta,” she said.

“Still. I mean, at mine it was mostly cereal or toast. You’ve got, like... herbs.”

She smiled, politely.

He looked around the flat as he always did, eyes flicking between bookshelves and prints and the old oak sideboard from her grandmother. He touched none of it. His world was glossier—open-plan kitchens, Bluetooth speakers, gin in tins. Her flat, with its worn throws and heavy mugs, probably felt like someone else’s grown-up life.

He gestured vaguely. “All this stuff—it’s mad. I dunno how you live like this.”

He meant it admiringly, she thought. But it landed crooked.

“I don’t know how I do either,” she said, too lightly.

On the radio, a voice broke in—the BBC presenter, introducing a clip. “The death toll in the UK has risen by a further 115...” She clicked it off.

After dinner, he offered to wash up. She let him. He used too much washing-up liquid, didn’t rinse properly, left water pooled around the taps. She waited until he left the room before wiping it all down, her movements efficient, practised, maternal. Casting a critical eye over his haphazard work. The things she hadn’t known would matter now did.

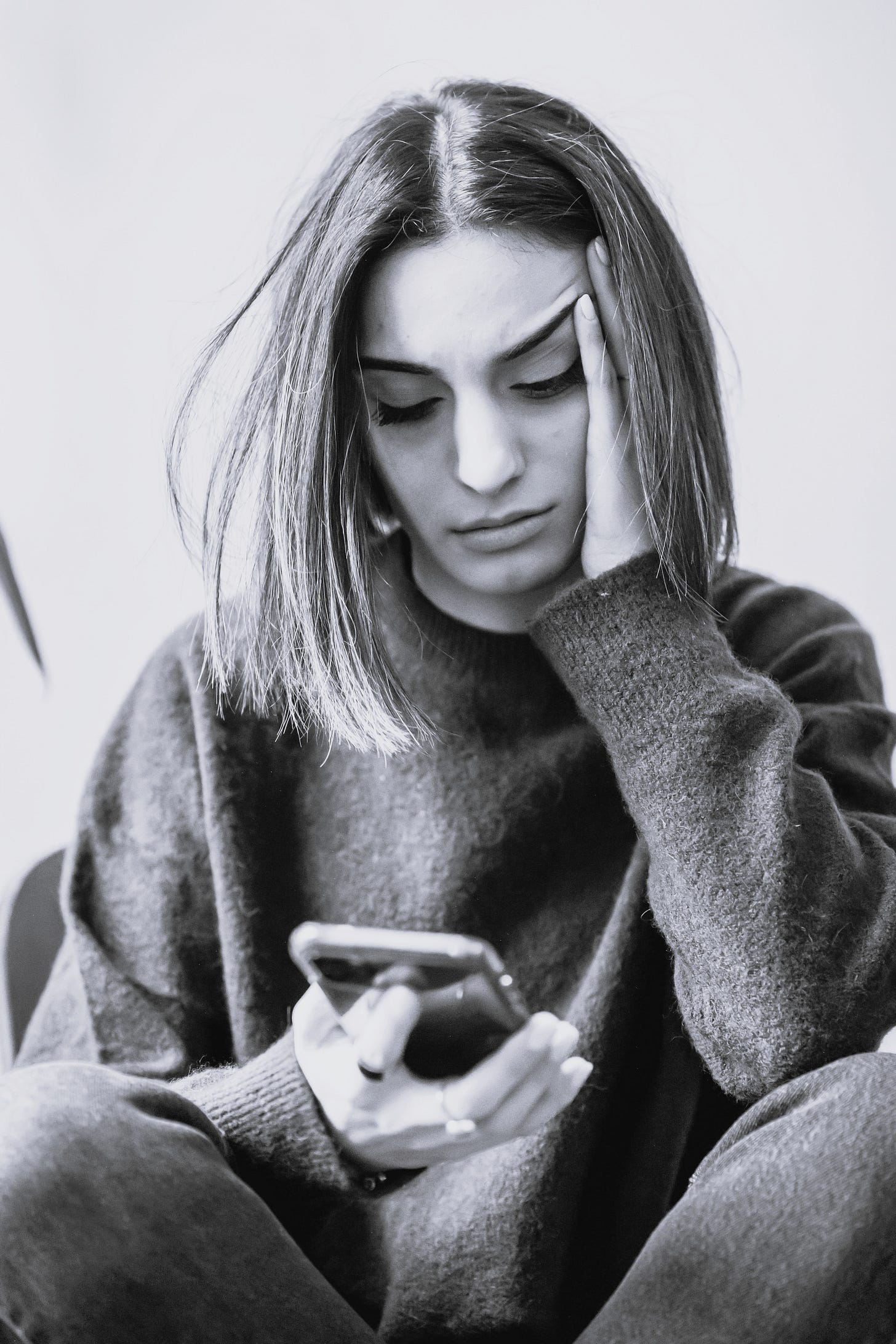

She wandered into the bedroom and sat on the edge of the bed. The flat was too warm. She’d started getting headaches again. Headaches that crawled in behind her eyes and made the air feel heavier. There was a pressure in her chest, lately. Not panic, exactly. Just the sense of her mind folding inwards. She had thought company would help. But it hadn’t.

She glanced at the framed photo on her desk—her nephew, his face beaming, sun-bleached hair stuck to his forehead. He’d just turned nineteen. Sam, barefoot in the next room, was barely older. A cold slick of shame moved through her. This wasn't a romance; it was a proximity. She felt her stomach turn.

He knocked softly on the doorframe. “You okay?”

She nodded. “Just tired.”

He hovered. “Want to watch something?”

“Maybe in a bit.”

He sat on the floor, pulled his hoodie over his knees. “Feels like nothing’s real. Like we’re in a waiting room and no one knows what for.”

She looked at him, then away. He was kind. Eager. Trying his best to comfort her. But it was all wrong. The passion had bled out, like heat from skin after the touch is gone.

He started to say something, then stopped. Rubbed a hand through his hair.

“I keep thinking I should be doing more. Helping. I dunno.”

“You don’t have to prove anything.”

“I know. But it’s hard. I feel like I’m... in the way sometimes.”

She didn’t respond. Because he wasn’t wrong.

He went to the kitchen, flicked the kettle on, then off again.

Behind her, he said quietly, “Do you want me to sleep in the other room tonight?”

She turned. He was standing with his hands in his hoodie, shoulders slightly hunched. That nervous smile.

“No,” she said, and meant it. But she didn't cross the room. Instead, she pulled her cardigan tighter around herself.

He looked relieved at her answer, but the nervous smile remained. “Okay. Good. It’s just... you get this look sometimes. Kinda like my mum when I’ve messed something up.”

The words landed like a physical blow. Clara didn't move.

“I’m just going to get some air,” she said, turning toward the window and the relentless drizzle outside.

She didn’t wait for a reply. The air by the window was still thick with steam and anchovy.

She pressed her forehead to the glass. Outside, the drizzle hadn’t stopped. Neither had the feeling.